The Etruscans have long been considered an extraordinary people, shrouded in a veil of mystery due to their indeterminate origin. They continue to intrigue us because of their differences with other ancient civilizations, such as the Roman and Greek, but especially owing to their fascination with the divinatory arts and the afterlife.

They even had their own status, characterization and language. A society with an outward focus but simultaneously tied to its own rituals. To get to the heart of the Etruscans, we must go back to the period from 1100 BC to the last phase of Roman Republic during which, with the Lex Iulia of 90 BC, they became Roman citizens.

The Etruscans founded cities between Latium, Campania, Emilia Romagna and Lombardy, all the way to Corsica. But Tuscany was a key part of the rich and fertile expanse of territory known as Etruria, a region that still preserves the precious legacies of this population.

Many of the Dodecapolis—the Etruscan city-states—were located here, namely in: Arezzo, Chiusi, Chianciano Terme, Cortona, Fiesole, Volterra and Populonia, but also in Roselle, Vetulonia and the fascinating Pitigliano and Sorano, places rich in important artifacts, starting with acropolises with remnants of temples, along with urns, grave goods and grand walls.

Cultivation, farming, trade, exploiting resources for livelihoods ... The Etruscans worked stone, seemingly so immutable, furrowed incredible shapes in tuff and delicate creations with alabaster. They even found fruitful mineral deposits, exposing alum, silver, iron and copper, especially on Elba Island. The Etruscans then worked the land with skillful farming techniques. Unsurprisingly, the Valdichiana area is known as the granary of Etruria. Products such as oil and wine are also said to have been plentiful parts of their meals.

Indeed, when traveling in Tuscany, so rich in excellences such as wine, olive oil and wheat, it is possible to savor what remains of the ancient bond between this land and the Etruscan people. From Chianti, Montalbano and Val di Chiana to Maremma, among the rows and olive groves of Barberino Tavarnelle, Montepulciano, Scansano, and Gavorrano for example, precious Etruscan artifacts have been found, most of which are safeguarded in the museums that enrich the heart of these splendid villages.

Following yet another lead, we find in the history of the Etruscans the importance of water, an irreplaceable element, essential for daily life. The centrality of precious hot springs today brings us to places like San Casciano dei Bagni, where ancient votive statues are still coming to light, as if by magic.

There is much proof of an independent people where women played a prominent role in society, present alongside their husbands and even represented with them in the sarcophagi.

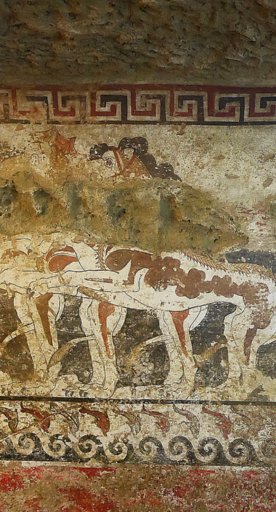

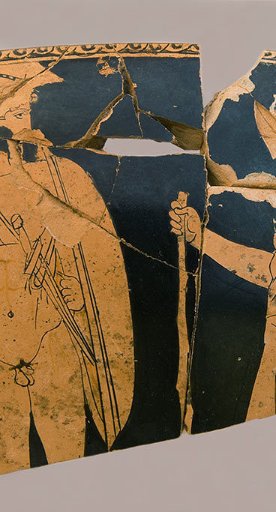

The otherworld was so crucial to the Etruscans that it prompted them to turn funerary complexes into works of art. Check out the frescoes in the Tomb of the Infernal Quadriga in Sarteano, the works of fine goldsmithing, bronze statues along with various kinds of decorated and painted pottery. To these are added objects of great value and fascination such as the statuettes from the Lake of the Idols, housed in the Casentino Archaeological Museum, the Shadow of the Evening and the Shadow of San Gimignano, the “Cappellone” of Murlo, and the sumptuous Etruscan Chandelier preserved at the Academy of Etrusca and the City of Cortona (MAEC) in Cortona, to name but a few.

Ambiguous curiosity aroused their concept of “the future,” long investigated by the rites of the priests. Some aspects of the present, however, suggest that the Etruscans never left entirely. In the aspirated “c” (/kʰ/) in certain consonants that Tuscans pronounce, perhaps hides the Etruscan spirit that has never ceased to enchant.